Click here to read the previous post, Adjusting to Life in Spain: An Irish-Spanish-American Thanksgiving

To read this post in Spanish, click here.

My boyfriend Alberto recently took me into the lion’s den of the Spanish experience: a local annual festival in a small town. With his family and about two million of their closest friends. All speaking Spanish. Rapidly. Spread out over a long weekend.

If my life in Spain were rated with the same proficiency scale for the language—Basic (A1-A2), Independent (B1-B2), and Proficient (C1-C2)—this past weekend would’ve shoved me right into C2. Again, this is life experience we're talking about, not ability to understand Spanish (where I teeter from A1 to C2 depending on many factors, including how many people are talking at once, how much slang they are using, and how hard I am crying).

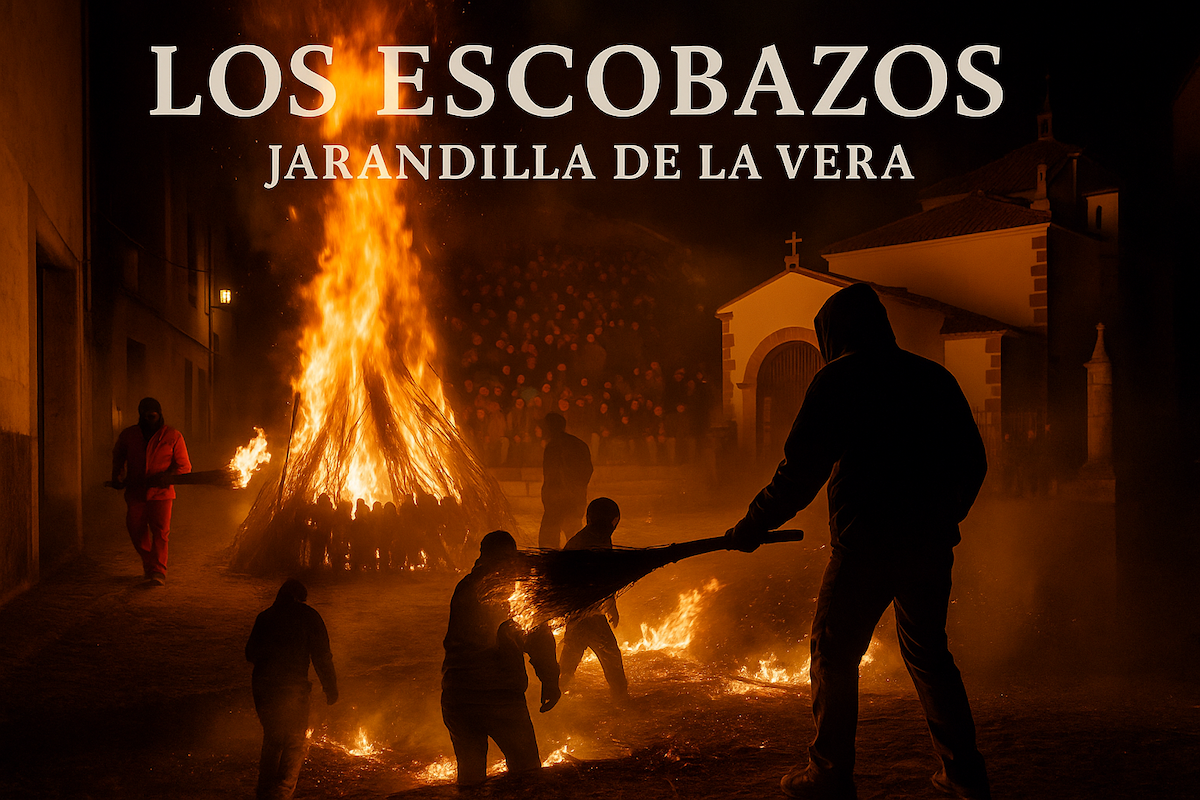

But back to the festival. It’s called Los Escobazos and it involves fire, music, singing, fire, alcohol, food and fire.

As Alberto and I drove the 2.5-hour route out to the country, he told me what I could expect.

What Is Los Escobazos Festival?

Los Escobazos (which translates to “the broom beatings” or “the broom whackings”) is one of the most unique annual festivals in Jarandilla de la Vera (or in all of Spain?). It involves brooms and fire and is celebrated on the night of December 7, the eve of the Immaculate Conception. (Naturally. 😳)

Like many winter fire festivals across Europe, it began as a way to mark the arrival of winter and guide shepherds home from the mountains. To make sure they didn’t trip and fall off the mountain or lose their way and wind up in the wrong pueblo, the shepherds would light bunches of branches on fire and use them as ancient flashlights.

These days, nobody’s coming down from the mountains, but locals still create escobas (brooms made from broom branches), set them on fire, and then walk through the historic streets of Jarandilla, playfully swatting each other with these flaming bushes.

“Wait, what?” I turned to Alberto. “What do you mean playfully swatting each other with fire??”

“Don’t worry,” he assured me. “You’ll be wearing protective clothing.”

“Protective clothing is needed? I’m feeling a little worried here.”

“Oh, there’s no need to be worried. Before the fire really gets going, we’ll be walking around the town drinking a lot.”

“You mean drunk people will be brandishing fire??”

I looked up “Lumbre de Sopetrán”, the caption on the poster above, and found that it means a sheltered, partially enclosed fire, usually for warmth, protection or everyday use—i.e. not a bonfire. Which, as far as I could see from the images on this poster, is a complete lie.

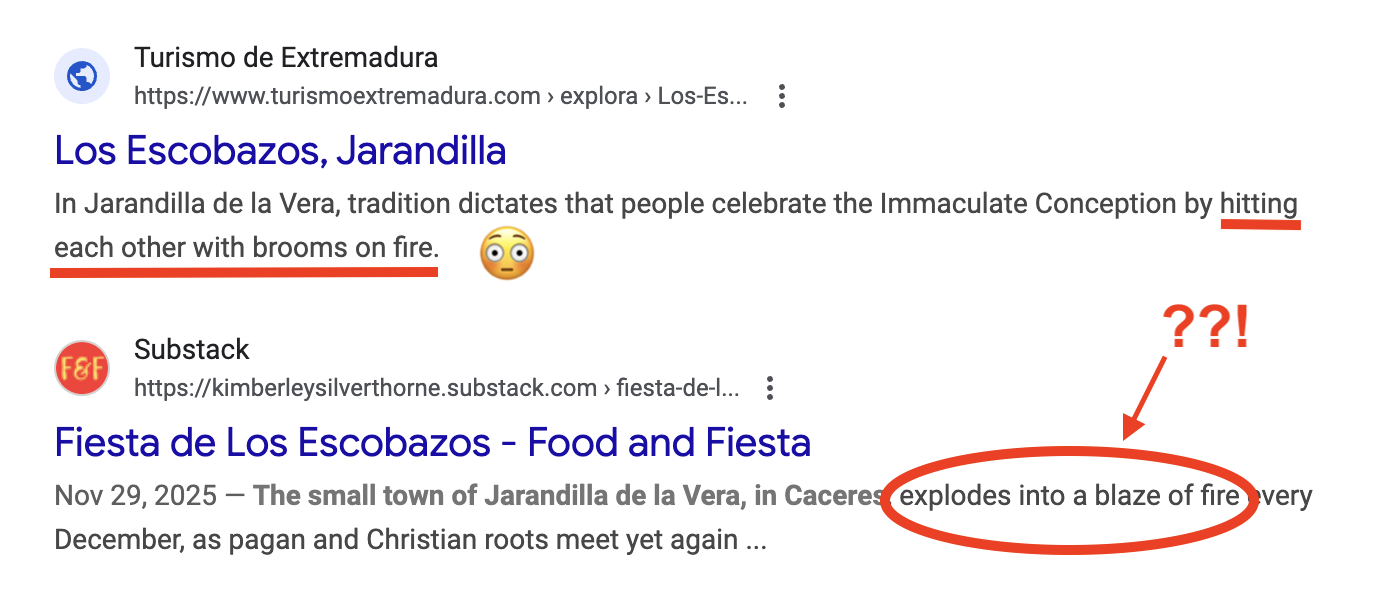

Plus, according to the top results in Google:

What the hell was I in for….?

Two Days Before the Festival

We and seven other family members arrived on Friday night, and within minutes the living room filled with rapid Spanish—names I didn’t know, customs I didn’t get, jokes I couldn’t catch, stories that moved faster than my brain could translate. I tried desperately to keep up, nodding along, smiling when I saw other people smiling.

They are all very nice and I genuinely like them, but it didn’t take long before my smile was dragging and my brain was exhausted. I stopped even trying to keep up with everyone and I didn’t want to constantly bother Alberto by leaning in and whispering “Now what are they talking about?” Eventually, I slipped out of the salón and up to the bedroom, grateful for the quiet but frustrated at my lack of Spanish comprehension.

Day one and my nervous system was already at DEFCON 4

As an introvert, I was really pushing myself here: New people, new language, new situation, new fucking FIRE festival. All at once. And I often find myself in such a paradox: I want to go to a weird festival where people I don’t know light things on fire, but once I get there my nervous system’s “fuel gauge” quickly hits E—not always dramatically, just steadily, the way you don’t notice until your car starts sputtering and all the other traffic just flies by you.

Fortunately, Alberto understands this about me, and we discussed beforehand how to deal with this. His emotional support made this new adventure entirely possible for me. <cut to goofy smile as I look at him>

One Day Before the Festival

On Saturday, I went downstairs to make myself my morning cup o’ tea. Alberto had awoken before me, and I expected to find him in the kitchen. As I descended the stairs, I heard. . .voices overlapping, a burst of laughter, chairs scraping, cutlery clinking.

Overnight, the house had filled with his family, plus extended family and friends, putting the headcount under this roof at about 12-14. I felt that familiar tightness in my stomach. And the fire festival hadn’t even started yet! I soon discovered that, including friends and family who were staying at other places around town, our group was about 35.

After breakfast (or lunch, depending on which country you come from), a small group headed out to the countryside on the outskirts of the pueblo to create escobas. As mentioned, they are brooms made from bundles of dried retama branches, which are the plants traditionally used to make brooms, hence the familiar name of this plant: broom branches.

Alberto and I arrived just as they were finishing up, so we didn’t actually contribute. I felt a small, unexpected pang of regret, in part because I’d missed the activity itself, and in part because it was another reminder of how I wasn’t quite fitting in. However, I did take this photo.

Once we returned to the house, Alberto’s sister and a handful of others were preparing the garage for a pre-game celebration. I asked his sister how I could help (cherishing these simple one-on-one conversations) and she immediately put me to work. I was grateful for the task which allowed me to contribute and not just stand there going “Qué?”

Two long tables were filled with food: cheeses, chorizo, jamón, chips, migas, wine, beer, vermouth and soda, and many other Spanish favorites. By the way, migas means "crumbs" in Spanish and is a traditional dish made from stale bread fried with garlic, oil, and sometimes meat. This was the biggest pan of it I’ve ever seen!

The speakers were set up and the music started. And of course how can you not dance?

Hoodies had been made up for our group, and—rhythmic music in background, vermut in hand—I felt like part of a gang for the first time in my life. Not a very tough gang, but a gang nonetheless.

Because most people knew each other, or at least knew the language, I found myself wandering out of the garage, hovering at the edges, and observing the goings on in the street. It felt easier to stand back and observe than to try to engage with such a large group of people (unless there was an opportunity to speak with one person at a time, which I jumped on).

The main plaza was less than half a block from where I stood and I could see them starting to build the “scaffolding” to the main bonfire that would be blazing tomorrow. A few people hung around watching. The bar next door had a couple of outdoor tables, and a handful of locals were standing around them in their winter coats drinking beer and wine.

After catching up with old friends and cousins, Alberto came out and we took a little walk, which was nice; it allowed me to breathe. When I’m with him, I always feel relaxed, comfortable and safe. We could see the excitement and anticipation building up in the pueblo. A couple people had built a small fire outside the church as they watched the main bonfire being constructed.

An hour or so later, we came back home to find that the bonfire scaffolding and the group at the bar had grown quite a bit!

Back in the garage where the fiesta was going full swing, we snapped pictures of our group having a great time (helped out by a couple of delicious caramel vodka shots). We had brought a portable photo printer, and printed pics, a minute later approaching the person or people with tangible evidence of their merrymaking. We also hung the photos around the garage.

Finally, the singing and dancing wound down, and then half our group decided it was time to go out and hit the bars. Alberto and I stayed in, and I let my nervous system finally exhale.

And the real intensity hadn’t even started yet!

The Day of the Festival

At breakfast, I sat at the table with about eight others for a good twenty minutes, smiling, nodding, concentrating so hard my head hurt. I didn’t understand much Spanish, but goddamit I gave it the ol’ college try!

Honestly, the difference between understanding your non-native language one-on-one versus with two or more native speakers is as vast as the Grand Canyon. Between the cognitive overload of multiple voices and overlapping speech, the linguistic variation of accents, dialects, slang and tones, and the lack of context of the subject that’s being talked about, I’m surprised I’ve made any progress with Spanish at all.

I was easing into DEFCON 3, overloaded but still technically operational.

That afternoon we headed out on the Ruta de las Bodegas (“wine route”), in which a group of anywhere between 20-50 people walked from one home to another for wine or beer and tapas.

I mostly walked next to Alberto, listening more than speaking, taking everything in more than actively participating, and just letting the group energy carry me along for the experience.

You could feel people’s excitement growing as they chatted and laughed and sang, and I was starting to see some hints of the fires to come.

By the way, all these homes we went to were voluntarily involved; it’s not like we just walked up to random people’s houses! The houses that participated had this sign hanging up out front:

As the sun went down, more and more people filled the streets, starting little fires on the cobblestones, carrying small burning brooms and generally filling the town with firelight and sparks.

The last stop on the Ruta de las Bodegas was our own home, and after eating, drinking and dancing some more, the time had finally come.

We needed to prepare for Los Escobazos.

Alberto took me to a closet in the garage filled with old but sturdy jackets, pants, shoes and hats. There were plenty of different sizes, and I finally put together a Los Escobazos outfit that fit me well: a black toque (knitted wool hat), a large, navy-colored army-type jacket with a collar, thick black jeans, and ash-smeared sneakers.

“You’ll be protected from the fire in these clothes,” said Alberto as he tucked every last strand of my hair under the hat.

Then I noticed a quarter-sized burn hole in the jacket. “Are you sure about that?”

“Don’t worry, the person who last wore that is still alive,” he said. “I think.”

I laughed nervously as he led me out of the garage into the noisy street. I paused, taken aback at how smoky the air had become. The narrow cobblestone streets had an eery feel to them: The darkness was strangely lit up with muted amber light from all the fires and the air was warbled from the smoke, as if we were underwater.

We headed to the plaza where the procession would start, dodging playful and not-so-playful swatters and skirting growing bonfires in the street.

As we got closer to the plaza, the noise of thousands of people grew louder and ash rained down on everything. The streets were filled with people lighting their escobas from other escobas like shared cigarettes, others swinging their flaming bundles around in circles, embers flinging out like rain drops, and still others simply wandering and singing.

Everyone was having fun, laughing and shouting, but sparks flew close enough to sting my cheeks, smoke burned my throat and my eyes were watering. It was hard to see clearly. I coughed, half covered my eyes and clung to Alberto’s arm as he led me through the chaotic crowd. It was starting to feel less like a festival and more like a war zone.

I kept watching my step, afraid of tripping, afraid of traipsing through the many fires on the ground and igniting like a paper napkin, but also afraid of missing something if I looked away. I was here to experience this festival and I wanted to document it all. I had my phone in hand, taking pictures and videos while dodging random bonfires and leaping out of the away from flaming escobas and enthusiastic revelers, hoping I was getting some good shots.

The plaza was jam-packed with people waiting for the procession to start.

And then it did.

When the procession finally began, all the random noises of the crowd seemed to funnel into one noise, and suddenly everyone was singing a song: Canción de los Escobazos. Riders in old costume passed slowly on donkeys and horses, embodying shepherds and villagers from earlier centuries. For a moment, I felt like I’d time traveled 500 years into the past.

From this plaza, the procession wound through the narrow streets to the other plaza, smaller but with the more important church, Ermita de la Virgen de Sopetran (Hermitage of Our Lady of Sopetrán—“virgin associated with protection and refuge”). This is where they’d been erecting the main bonfire “scaffolding” all day.

Once everyone arrived at this other plaza, we stood watching the giant bonfire roar skyward, and I felt the heat hit my face even at 100 yards (90 meters) away, sparks shooting into the dark sky. I felt both awed and completely wrung out.

Alberto took my hand and led me into the house, upstairs and into a back bedroom where we watched the bonfire from the balcony. We were still close enough to feel the heat, but out of the crowd.

By this time, I was at DEFCON 2—glitching, words blurring together, Spanish and English equally inaccessible. My system was done.

The Day After the Festival

Even though I’d slept well and genuinely enjoyed the weekend and Alberto’s family, I could feel something unraveling as we packed up. (DEFCON 1 didn’t actually hit me during the festival—it hit once I was back home, in the safety of my own refuge. I didn’t leave my apartment for two days. I barely spoke. I needed silence, solitude and tranquility the way you need water after a long hike.)

We all pitched in and cleaned up the house in Jarandilla, packed the cars, said our goodbyes. The town felt calmer now, emptied out, as if it too were recovering from exhaustion.

Before we left, I walked over to the plaza and stood where the bonfire had burned the night before. Only ashes remained—cold, black, still smoking, rather unremarkable. It was hard to believe how much intensity they’d held just hours earlier.

Was the night of fire overwhelming? Absolutely. Did I enjoy getting to know Alberto’s family more? Definitely. Am I glad I experienced it? Believe it or not, yes.

So would I go back next year? No effing way. My nervous system has filed a formal complaint.

On the other hand, you don’t move across the ocean to a new continent, country and culture just to recreate your old, carefully controlled routines. When I landed in Spain, I promised myself I’d say yes more often—even when yes comes with smoke, fire, overwhelm and a full nervous-system reboot.

So. . .check back with me in a year. I might still say no. Or I might be lighting my own escoba.

Click here to read the next post, Adjusting to Life in Spain: [TBA]

Note: All photos taken or created (using DALL-E) by Selena Templeton, unless otherwise noted.

If you enjoyed reading this travel blog, check out some of my other adventures:

Adjusting to Life in Spain: Dating in My Non-Native Language

Adjusting to Life in Spain: Using the Spanish Healthcare System

Adjusting to Life in Spain: Damn, I Can’t Find My Favorite Products Here!

From Fiesta Invites to Flamenco Nights: My Adventure in Spain

My Road Trip to the Four Corners: Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona