Click here to read the previous post, Adjusting to Life in Spain: A Day Trip to Alcalá de Henares

I can’t believe I’ve lived in Spain for a year now (whaaaaat??!). On one hand, it seems like just yesterday I landed on this continent with only five suitcases to my name. And yet, on the other hand, I feel like I’ve packed five years’ of life into these past twelve months.

I’m sitting at an outdoor table at my favorite café in a little plaza under some trees. Honestly, it’s a little too hot to be sitting outside, but I’m trying my best to become a true Spaniard. (Waving a colorful abanico (hand fan) in front of my face helps!) Neither rain nor sun nor heat nor cold can stop a Spaniard from sitting outdoors while enjoying a refreshing drink and good company!

And that makes me think: Am I anywhere near to being a(n honorary) Spaniard or am I still very much a guiri (tourist)?

Now that I’ve celebrated my one-year anniversary of living in Spain, I thought I’d peruse memory lane to see what I’ve learned from my time in this country, and if or how I’ve changed.

What I Learned From My Year in Spain

Keep in mind that A) I’ve lived only in Madrid all this time, B) these are my personal (well, some are objective) observations, and C) when I say “learned” I basically mean “noticed,” “experienced” or “thought of for a second before another thought took its place.”

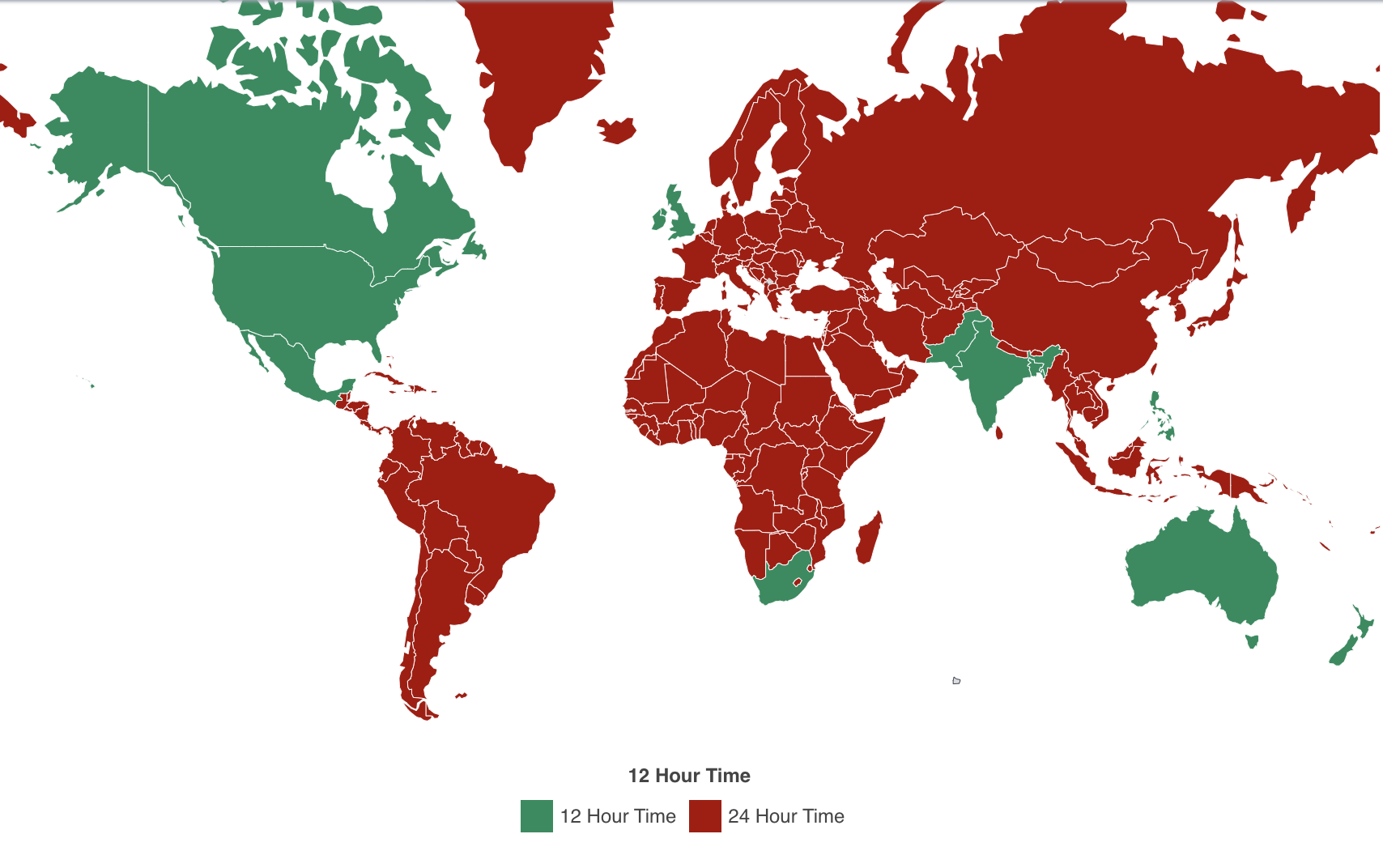

The 24-Hour Clock

I’m pretty impressed with myself that I can now look at a digital clock here in Spain and actually know what time it is. In Europe – in fact, in the majority of the world: 60–70% – the 24-hour clock is the default format.

Source: World Population Review

But because until recently I had lived all my life in Canada and the U.S., the 24-hour clock was as foreign to me as, well, the 24-hour clock. A year ago, a Spaniard texting me the time and place where we’d be meeting drove me into full panic mode and to combat that I’d just show up a day early and wait for them to appear.

Today, I glance at a clock that says 20:21 and think “Hm, that clock is four years slow.” Kidding. But seriously, rather than doing awkward math on all my fingers, I now see that time and immediately register it as 8:21 p.m.

I Now Own a Bathing Suit

The first time I visited a friend in La Adrada, a small town outside of Madrid, she said, “It’s so hot today. Let’s go for a swim in the river!” When I told her I didn’t own a bathing suit, her jaw dropped. Then this summer A, the guy I’m dating, said, “It’s so hot today. Come over and let’s swim in the pool!” When I told him I didn’t own a bathing suit, his jaw dropped.

Even though I lived in Vancouver and Los Angeles which are both on the coast, I never really got into swimming. I think part of it was the beach environment: accidentally swallowing salty seawater, being tossed about by waves, seaweed tangling around your ankles, sand getting everywhere, and little shade to protect those of us who are pigmentally challenged.

But in this last year, I saw that swimming (in rivers, pools, the ocean, puddles if they have to) is much more embedded in everyday summer life in Spain than it typically is in the U.S. or Canada (at least in my personal experience) – especially in small towns or the countryside.

I suppose that Spain’s hot summers and mountainous terrain (especially in certain regions like Extremadura, Castilla y León and parts of Andalucía) make gargantas (mountain streams), rivers and natural pools ideal for cooling off — and, in my not-so-humble opinion, often better than crowded beaches or chlorinated pools.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say that it’s the law in many small towns that you have to swim in rivers in summer. Okay, maybe not the law, but as close as it gets without a visit from the Guardia Civil in chanclas (flip-flops) handing you a floatie and pointing toward the water. You’ll usually find stone steps for easy access to the river, public bathrooms and chiringuitos (literally “beach bars,” but better known to us gringos as snack bars or beer stands).

So, miracle of miracles, for the first time in fifteen years, I now own a bathing suit and I’ve swum in pools and rivers. (I think I can stop right here and declare myself a true Spaniard!)

Always Make a Reservation

When you’re the one planning a dinner or lunch out, always make a reservation. This I learned the hard way. Where I come from, it’s standard to make a reservation for a busy restaurant on a Friday or Saturday night, but otherwise not usually necessary. Here, it’s customary to make a reservation even at a chiringuito (snack bar) at a local river.

Okay, maybe that’s an exaggeration, but only a little. I think it’s quite common (and necessary) to make reservations even for casual meals at hole-in-the-wall places because of a few reasons:

Fixed mealtimes: Unlike North America where many restaurants serve food continuously from lunch through dinner, Spanish restaurants operate on strict mealtimes and close between those two meals.

Longer dining experiences: Meals in Spain are usually long drawn-out social events, and not just about eating. Since people stay at their table for hours and no waiter is ever going to guilt-trip you into leaving, it limits how many groups a restaurant can serve in an evening.

Smaller venues: Many Spanish tabernas, bodegas or restaurants are small, family-run places with limited seating, unlike the larger chains common in North America.

Social dining habits: And, finally, I think it’s more common in Spain to go out in groups of friends or family, not just as couples or solo diners. Tables for more people are harder to find on the spot, so reservations become essential. Note: On more than one occasion, I’ve shown up by myself and have been given a table (for one. In the corner. Facing the wall.)

My Voice Is Different in Spanish

This observation was first made by A, the guy I’m dating, after I’d left a couple voice messages for him, some in Spanish and some in English. He said that my voice is deeper in English and “sweeter”, more “innocent” sounding in Spanish.

Anyone who knows me is probably surprised to hear this. I know I was. But then I listened to my voice messages in both languages and realized: Oh crap, he’s right.

It’s not that I’m not a sweet person, because I am (or can be as long as you don’t fuck with me! <shakes fist in air>). It’s that in English my voice tends to reflect my confidence in the language. I don’t mean to toot my own horn, but as an English Major and a writer/editor, I’m extremely comfortable using my native language. In fact, I’ve gotten out of several tickets (parking, speeding) based on my oral defense in a court of law. I also convinced a lawyer (in a separate issue, believe it or not) not to sue me after thirty minutes of verbal swordplay and witty repartee.

All this is to say: My confidence in my first language comes across as a comfortable lower register, while my lack of confidence in my second language comes across as a ten-year old lying to her father about the rocking chair she claims she didn’t break.

Answering the Apartment Intercom

Every time my fucking apartment intercom buzzes I jump a foot in the air. Here, when a delivery person or postal carrier or gas meter reader needs access to the building, they just buzz every apartment and wait for someone to answer – and someone always let them in.

In the U.S. and Canada, no way José. In those countries delivery persons and postal carriers (gas meter readers don’t exist) have the building code or a special key. And if someone buzzes you saying they need access to the building, you usually tell them you’re on to their scam and then hang up.

That’s because of the cultural and practical differences between these countries.

In Spain:

There’s a general cultural attitude of openness and informality, and less paranoia or liability concern. People often assume a delivery is for a neighbor and just let them in.

Spaniards are used to communal life — shared buildings, plazas, bars, terraces. There’s an underlying assumption that people respect the shared environment. So things like “buzzing someone in” aren’t viewed as risks, but as normal courtesies.

It’s simply how the system works — delivery personnel don’t usually have building codes or keys — and everyone understands that.

In Canada and the U.S.:

Canadians/Americans are more individualistic, with a greater emphasis on personal boundaries, property protection and “stranger danger.” There’s just a stronger cultural suspicion of the unknown, which creates a heightened sense of needing to protect yourself.

Many buildings have explicit rules like “Do not buzz in anyone you don’t know” so tenants may be liable for unauthorized entry.

Most delivery workers and postal carriers have key fobs, codes or access cards provided by the building manager or USPS system (like the USPS’s Arrow Key).

So after one year here, have I gotten used to it? Hell no! But not because I’m nervous to buzz unknown people in. Because the buzzing causes me to collapse to the floor in near cardiac arrest and by the time I crawl to the intercom the person who needed to get in has already come and gone.

Invitations Always Include Your Significant Other

I would say a good 80-90% of the time when someone invites me to dinner, drinks, their house, they make a point to also invite my boyfriend – even when they’ve never met him. In contrast, in the U.S., the invite doesn’t usually include partners.

And I’m not talking about weddings or other big events, where you have the option to check off a “plus one.” I’m talking about a newish friend that you made in your new city who asks if you want to go out for drinks or come over to her place for lunch. “Bring your boyfriend!” or “Will your boyfriend be joining us?” is often said in the same breath (or the same text; who am I kidding that I talk on the phone?).

I think this just reflects the Spanish communal attitude, as mentioned in the section above, where the phrase “the more, the merrier” is a way of life. Here, hosting is about warmth, not formality. It’s about making others feel welcome, not about white-knuckling the guest list. If you're being invited, they see your partner as part of your life, so he/she should feel welcome, too.

American and Canadian culture often focuses on the individual rather than the group, so a dinner or even drinks invite is frequently understood as a one-on-one thing, not necessarily extended to the person's entire social circle. I think social circles in North America tend to be more compartmentalized; you don’t always mix your work friends, gym friends and neighbors.

Linguistic False Friends

In this example, what I learned is that the Spanish language is bonkers.

Fruto seco does not mean dried fruit, even though fruto means “fruit” and seco means “dried”. Nope, fruto seco means “nuts”. I always thought nueces meant “nuts” but it doesn’t. It means “walnuts”.

Which makes the name and type of this store mind-bendingly confusing:

Frutería means “fruit shop”. So this is a nut fruit shop. A fruit shop that sells nuts. Which Google calls a grocery store. No wonder it rates only 3.2 out of five stars….

You May Also Like: Adjusting to Life in Spain: “Llevar” – Adventures in Spanish Vocabulary

Bookstores on Every Corner!

Well, almost every corner. But honestly, it seems like every time I step out of a café, bar or store, across the street is a librería looking me right in the eye, daring me to come in and just browse….

One caveat: This refers to only the central district of Madrid (el centro) – the official district comprised of six barrios: Embajadores, Sol, Chueca, Malasaña, Palacio and Cortes – not out in the ‘burbs.

But then I got thinking, how many book shops are there in this area? Well, after typing that question, I realized that the answer is a little hard to come by, as:

Google results simply turn up “best bookstores in Madrid” (I didn’t ask for best bookstores)

Perplexity comes up with “there are at least 10 notable bookstores in Madrid’s el centro” (I didn’t ask for notable bookstores)

ChatGPT says there are approximately 15-20 notable bookstores in this area (better, but I still didn’t say notable)

A website called Librerías de Madrid (Madrid Bookstores) claims there are 145, which I suspect includes all of Madrid, not just the downtown area.

Finally, I used ChatGPT’s Deep Research tool, which came up with 30-35 bookstores in the specific area of el centro, based on public directories and local listings. It categorized them by large chains, independent bookstores, second-hand booksellers and specialty book shops. Based on my own walking around experience, I’d say this sounds about right.

But, more importantly, there are bookstores on every corner!!!

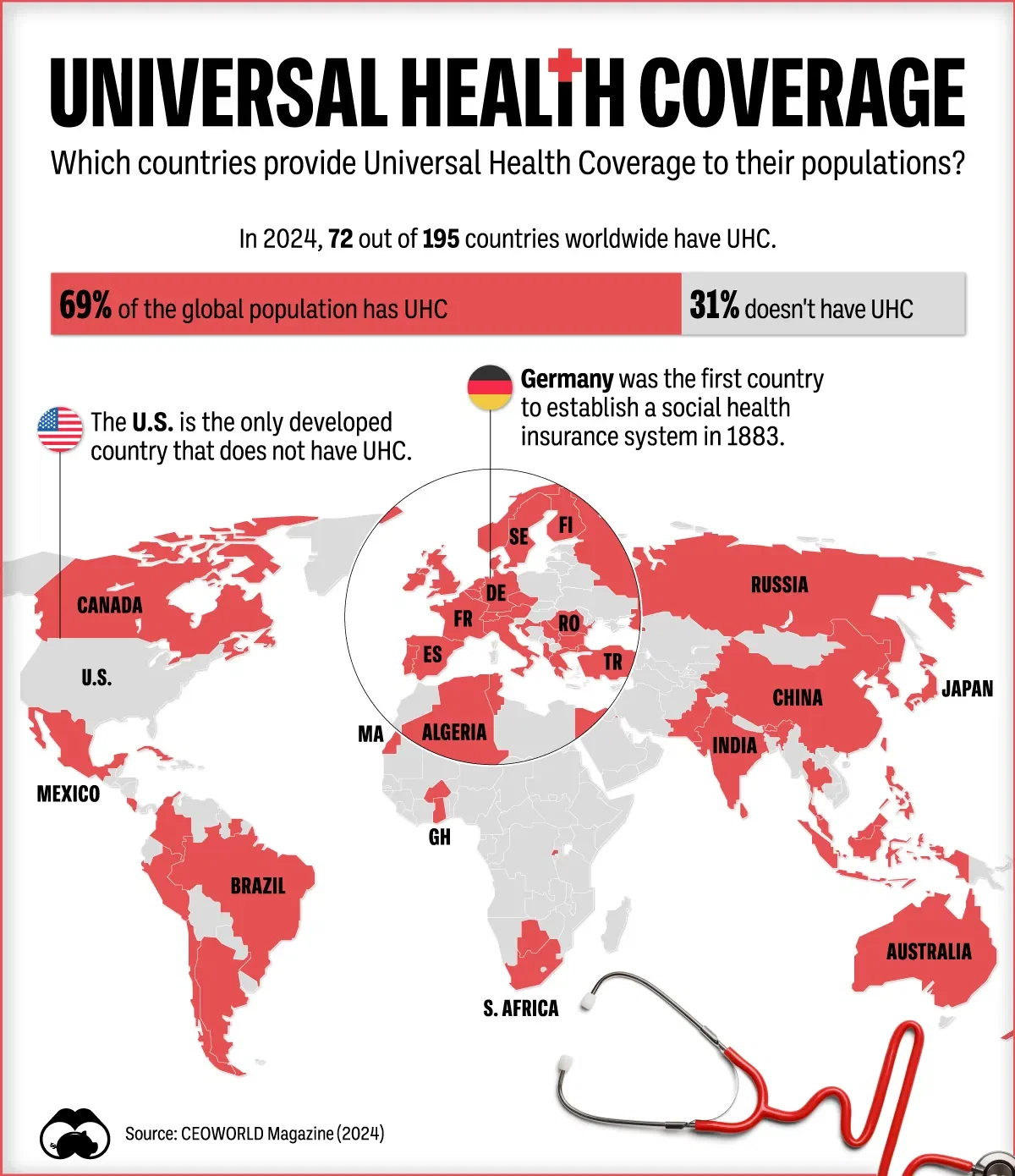

You’ll Never Get a Bill at a Hospital

As I’ve written about before, the difference in healthcare between the U.S. and Spain. is tantamount to a human violation. And not just Spain, by the way; as of 2024, 72 out of 195 countries (which represents about 69% of the global population) have implemented universal healthcare systems.

A country is considered to have UHC if:

All residents have access to necessary healthcare services.

Costs are either fully or significantly covered by the government (via taxes, insurance or both).

No one is excluded due to income, employment or pre-existing conditions.

I’ve been to see my doctor and to urgencias (the emergency room) many times in the last year, and I’m still surprised-slash-relieved that I’ve never had to open my wallet upon leaving.

Coming from Canada, I already had experience with universal healthcare, but after living in the U.S. for over twenty years, the “free healthcare” neural network in my brain had shorted out like a dial-up modem trying to stream Netflix.

Public Transportation

Taking the metro/bus/train is soooo convenient – even when traveling to small towns 1-2 hours away (El Escorial, Buitrago de Lozoya, Ávila, Alcalá de Henares, La Adrada)! Without a car, I could’ve never taken these day or weekend trips outside the city in my previous life. Keep in mind that this is compared to Los Angeles (and even Vancouver) where public transportation is more of an afterthought than other cities like New York or London.

Spain (especially Madrid) is far ahead in terms of coverage, frequency, affordability and national integration, while Los Angeles remains heavily car-dependent and Vancouver does well by North American standards, but still lags behind European cities like Madrid.

Since I am currently without a car, I am extremely grateful for the convenient public transportation in this city and country.

You May Also Like: Adjusting to Life in Spain: Differences Between Spanish and American Culture

Washers but no Dryers

When I first moved to Spain and was looking at apartments, I noticed that they all had washing machines, but no dryers. Compared to my time in Los Angeles and Vancouver, where apartments typically do not include a washer or dryer – instead, there’s usually a communal laundry room in the basement of the building – this felt quite luxurious. To be able to do my laundry on a Sunday morning while still in my PJs and fucked-up hair has been life changing!

And as for the lack of dryer in Spanish apartments, well, every home has an indoor clothes drying rack.

I’ve come to adapt to this way of life. Sure it feels a little 1950s — like I should be ironing handkerchiefs in curlers, canning preserves and gossiping with the other housewives — but once you get used to it, it’s kind of fun.

I’ve discovered that it's very common in Madrid (and across Spain) for apartments not to have a dryer, and here’s why:

Climate makes dryers unnecessary. Spain, especially central and southern regions, enjoys plenty of sunshine and — key word — dry air, making line-drying clothes fast and easy. Plus, Madrid has a dry climate even in winter. So clothes dry quickly indoors or outdoors, often within a few hours. (Or 20 minutes on a hot July day with the French doors open!)

Energy efficiency & cost. Dryers use a lot of electricity, and Spain’s electricity prices are among the highest in Europe. So avoiding a dryer is a simple way to save money and reduce energy usage.

Space constraints. Most Spanish apartments — especially in city centers like Madrid — are on the small side. There's generally not enough room for two large appliances in the kitchen or laundry area, unlike North American homes (even some apartments) that often have a dedicated laundry room.

Cultural norm. Spaniards have grown up drying clothes on a tendedero (clothesline), so it’s just part of life. It’s normal to see sheets, undies and t-shirts flapping over balconies or on clotheslines strung across interior patios or exterior windows. There’s no social stigma around line-drying, unlike in some North American neighborhoods.

Dinner Followed Immediately by Bed

I’m still not used to the fact that Spaniards dine at fucking midnight and then go right to bed on a full stomach. Okay, I exaggerate a little bit.

But honestly, la cena (dinner) in Spain is typically between 9–11 p.m. and that just feels blasphemous to me. Between 9 and 11 p.m. I am usually preparing for bed (or thinking about preparing for bed), not preparing the last meal of the day.

To be fair, this isn’t a typical dinner that we have in North America (which is usually the biggest meal of the day). This one is lighter and might include a soup and salad, a tortilla española (omelet) or a few tapas. And, of course, wine. But still….

This is one custom I ain’t adapting to. I can’t eat a meal, not even a light one, and then hop into bed within the hour. Incidentally, I’d like to know what the stats are on acid reflux for Spaniards….

High Alcohol Consumption Without Intoxication

I’ve mentioned numerous times that Spaniards drink with pretty much every meal, including almuerzo (mid-morning snack) starting at 10:30 a.m. And yet, I don’t think I’ve seen even one drunk person in the last year. In L.A., on the other hand, I saw at least one drunk person per day (and, no, that doesn’t include in my own apartment).

Why the difference? Well according to my findings:

Drinking is cultural, not recreational. In Spain, alcohol (typically wine, beer, vermouth) is part of everyday life rather than a vehicle for getting wasted. It’s treated like a complement to food, conversation or relaxation, not an event in itself. In the U.S. and Canada, people often go out “to get blasted.” That’s the point. Yeesh.

Attitude over quantity. To expand on the above point, the cultural mindset here is basically “enjoy, don’t overdo.” Drinks are sipped slowly, often over the course of an hour or more, while chatting with friends or family. Being obviously drunk, loud or sloppy is often seen as embarrassing or immature, not funny or social.

Alcohol is paired with food. Spaniards pretty much always drink while eating — even with a late morning pincho de tortilla (slice of tortilla, or Spanish omelet). Even when going to a bar for a drink, you’re always served a basic (and free) tapa, like a dish of olives, nuts, chips or sometimes something more substantial like bread and cheese. Food slows alcohol absorption and reduces the likelihood of intoxication.

Lower alcohol by volume. Many drinks, like cañas (small beers), tinto de verano (red wine mixed with lemon soda — sounds weird but is actually refreshing and delicious!), or vermouth with soda, are lower in alcohol content. Portions also tend to be smaller (e.g., a 330ml beer instead of a pint, which is roughly 473ml).

Habitual, not excessive. Regular drinking in moderation builds tolerance and people here know their limits. There's less of the "binge drinking on the weekend" culture found in parts of the U.S., UK or Northern Europe.

Safe Country

When I first moved to Spain, I asked several people — especially women, who have a different perspective on safety than men do — if Madrid was safe to walk around in by myself. The answer was a hearty “YES.”

Spain has one of the lowest crime rates in Europe: It’s the 6th safest country in the world and the 4th in the European Union. And Madrid, a big city, is considered very safe, too, especially compared to many parts of the United States.

Here’s a look at why:

Violent crime (murders, assaults, armed robberies) is rare in Spain, and Madrid has one of the lowest homicide rates of any major European capital. Most safety concerns are non-violent, like pickpocketing in tourist areas (e.g., Sol, Gran Vía, on the metro).

It’s common and generally safe to walk alone in Madrid, even late at night. Many people eat dinner late and stay out past midnight, so the streets are still lively. Women often feel safer walking alone in Madrid than in many U.S. cities.

Police are around, but not aggressive or militarized. Laws around guns are strict — no widespread civilian firearm ownership — which contributes to lower violence.

Take a look at these crime rates:

So yeah, I feel perfectly comfortable walking through downtown Madrid at night by myself rifling through my thick wad of cash and whistling “Money, Money, Money.”

You May Also Like: Adjusting to Life in Spain: How Am I Improving My Spanish?

Weekly Parades and Holidays!

I live on a quiet street adjacent to a major street, so from my apartment I can always hear when there’s a parade happening, and from my balcony I can see it. And it seems like there are weekly parades in Madrid and national holidays for all the Saints and a few non-saints!

Ok, I'm exaggerating a little. Or am I? Let’s take a stroll down Rabbit Hole Lane….

Why are there so many holidays in Spain?

Catholic tradition: Spain has deep Catholic roots, and many local holidays are tied to saints' feast days, the Virgin Mary or religious events.

Decentralized system: Spain allows regional and local governments to declare their own public holidays.

Cultural pride: Each city and town has its own patron saint, with at least one local festival to celebrate — often with parades, music and street parties.

They just love a good celebration!

The community of Madrid observes twelve holidays each year, plus regional municipalities (cities/towns within the community of Madrid, such as the city of Madrid) can have two additional local holidays.

According to Public Holidays, these are the 2025 public holidays in Madrid:

Not too many, but of course those are just the public holidays. Spain also has a ton of saints’ days and other public celebrations.

In Madrid, for instance, there are several local holidays (with or without a day off) specifically tied to saints' feast days:

San Isidro Festival (May 15)

San Antonio de la Florida (June 13)

San Juan Night (June 23)

San Cayetano Festival (August 6)

San Lorenzo Festival (August 10)

Virgen of Almudena (November 9)

The best part is that when I’m on my balcony watching the parade, inevitably a neighbor from the next building over is standing on her balcony, also watching, and when I ask her what the occasion is, she always tells me.

Anyway, lest I fall down yet another investigational rabbit hole, suffice it to say: It can feel like there’s a parade, procession or festival passing by my house nearly every week. But am I complaining? No, I am not! Who doesn’t love a good parade in the middle of the week, day and street??

Drinking Fountains all Over the Place

In this past year, as I’ve explored numerous neighborhoods in Madrid, and towns in Spain, I noticed a lot of public drinking fountains. But they often look too fancy to drink from — that is, they look like ornamental fountains, not drinking fountains.

Source: Madrid No Frills

But it’s true — Spain has a large number of public drinking fountains, dating back to Roman and Moorish times, when they were building incredible aqueducts as if they were LEGO constructions. Madrid has 1,600 fountains and Barcelona has 1,700.

There are a couple reasons for making drinkable water so convenient:

Hydration needs: Spain, especially southern regions like Andalucía, experiences hot summers. Public drinking fountains provide an accessible way to stay hydrated while out and about, as most people are.

Social function: Traditionally, fountains were installed in plazas and villages around sources of water to supply the population with drinking water. These fountains became social gathering spots and were often designed with ornamental elements, blending utility with public art, as you can see from the pictures above.

Sustainable initiatives: Projects like the LIFE WATER WAY along the Camino de Santiago have installed many purified natural drinking fountains to provide drinkable water for hikers while reducing plastic bottle use.

Have the Right Expectations Before Moving to a New Country

In addition to just “learning” all these fabulous things about my new country, I was also thinking about how comfortable I feel — and have felt from day one. In a little over a year, I haven’t experienced any “buyer’s remorse” or “home sickness” or any other “holy shit what the hell did I just do??” moments.

I think that’s because I had the right expectations from the start — Spain wasn’t going to “fix” my life, nor was I going to be someone totally different over here — and the right reasons for making this giant move.

There was an article going around the ‘net earlier this year, written by an American woman who had moved to Spain after a couple of vacations here but returned to U.S. soil two years later because she came to basically hate it.

She felt she was misled about Spain and wished she’d better known what she was getting in to before moving: “The thing that really bothered me about them over there (was) their way of living and their way of doing things.” Read: I don’t like Spanish people because they’re too Spanish. What the shit, man??

It doesn’t take a detective to figure out why she felt disillusioned. She didn’t do her homework before moving to a whole different country with a different culture and language!

She had moved to the colder part of the country and was surprised that it was so cold. She bought a cheap house and was surprised that you get what you pay for. She enjoyed the relaxed lifestyle on vacation but was frustrated that many businesses close for a couple hours during the afternoon (siesta). She moved to the north of Spain where seafood is super popular and then complained: “After a while, I got really tired and grossed out with the Spaniard food.”

(FYI, that should be Spanish food; Spaniard food means food made from Spaniards. No wonder she was grossed out!)

My point is: When you move to a new country (or city, for that matter), you have to understand that there will a bit of a gap between your expectations and reality. So, first you have to be honest with yourself about why you’re moving (to quote a book title: Wherever You Go, There You Are). And secondly, you have to do your research — and that means go on one or more scouting trips. Not just a two-week vacation.

So was the reality of my move from Los Angeles to Madrid vastly different from my expectations? No. And, in fact, the reality turned out to be far better than what I’d prepared myself for.

My One-Year Summary in Madrid

If you’re still reading at this point, yay you! I thought I would provide a quick bullet point of the major milestones in my year here in Madrid:

Thanks to the fabulous Julia of Life in the Move, I got the first apartment I saw and fell in love with, and still love it. It’s a very European building on a very European cobblestone street in a very European part of town that’s close to everything I need, including the Royal Palace.

I quickly made some very good friends, including Colombian C (who celebrated my first birthday with me in Madrid), Americans R&E (whom I’ve adopted as my (young, cool!) parents in Spain), Spaniard L (who was there for me the minute I landed in this country), Canadian K (who comes from the same B,C. town as my aunt!), Irish L (who is a super fun fellow vermouth aficionado) and British M (who is an avid reader and conversationalist).

I traveled to El Escorial, Galicia, Buitrago de Lozoya, Ávila and Alcalá de Henares by myself or with a friend — and learned how to take short- medium- and long-distance trains!

I regularly go to a cata de vino (wine tasting) to learn about the wines of Spain (and that you order by the region here, not the grape, so if you don’t know the region, tough luck for you!) and, more importantly, meet some wonderful people, either new residents or travelers passing through.

I joined a dating app where my second ever date in Spain was with A, a Spanish man, whom I’ve been seeing for eight months and whom I adore.

A Spanish lawyer I know put me in touch with Barney Jopson of The Financial Times who interviewed me about moving from the U.S. to Spain, and my pic was on the front page of the paper!!

Then Noticias Cuatro, a news program that airs on Cuatro, a national television channel in Spain, interviewed me and my friend about moving from the U.S. to Spain.

And though I am not fluent yet, as was my goal a year ago, my Spanish has definitely improved more quickly than ever due to: living in a Spanish-speaking country, continuing my private Spanish lessons with my wonderful teacher, and dating a Spanish-speaker. Plus I’m reading books and watching shows and movies in Spanish, have changed my phone to Spanish and refuse to speak English whenever I have the mental strength.

But does all this make me a Spaniard? Well, a woman was asking a question in a bar in English, but the bartender didn’t understand her. She tried again, still no luck. So I translated for the waiter, who then responded, and the woman thanked me.

Another time a customer asked a waitress in a café where the closest hair salon was, and the waitress didn’t know. I, on the other hand, did, so I pointed them in the right direction. The waitress thanked me (in Spanish).

No, none of this makes me an actual Spaniard, but nor does it make me a tourist. What it does make me is an enthusiastic outsider with a newcomer’s curiosity, someone who’s come to love this country deeply, someone who drinks vermouth at all hours of the day, and someone who still doesn’t know how the fuck to order wine.

Click here to read the next post, Adjusting to Life in Spain: 6 Weird Spanish Foods I’ve Eaten

Note: All photos taken or created (using DALL-E) by Selena Templeton, unless otherwise noted.

If you enjoyed reading this travel blog, check out some of my other adventures: